INTRODUCTION TO MAHAYANA BUDDHISM

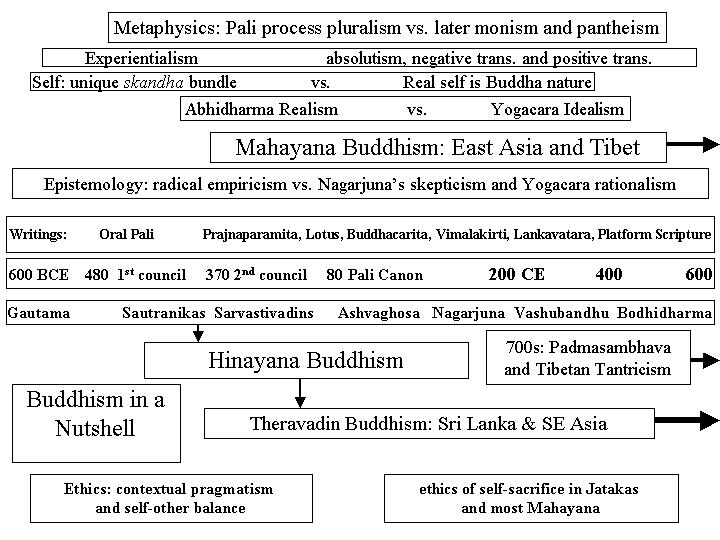

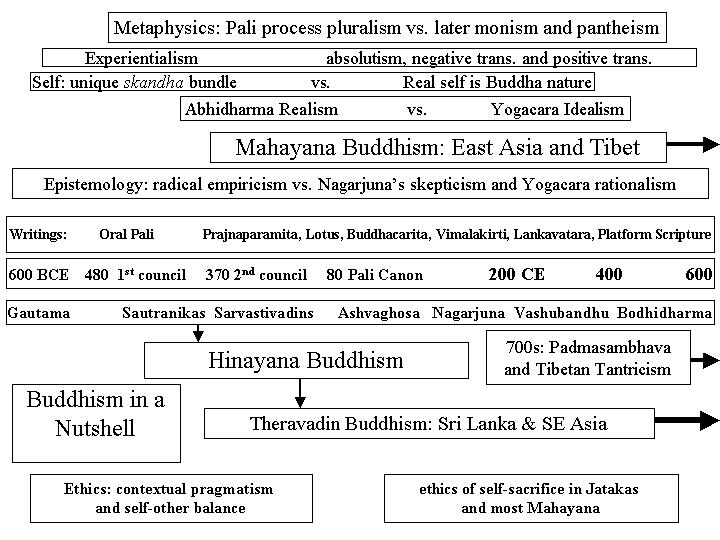

We should call the non-Mahayana schools "Hinayana" (small vehicle) rather than Theravadin, because the latter is only one of many sects that arose between the Buddha's death and the rise of Mahayana.

The title and existence of Bodhisattvas existed in pre-Mahayana schools, but the later innovation was that this "position" was now open to everyone.

The nature of Mahayana sutras:

1. all written in Sanskrit

2. written from 200 BCE to 400 CE

3. early ones do not disparage the monks; only the later ones do

4. preserved for 500 years by naga serpents!--hidden in trees and caves.

Mahayana authors produced treatises (sastras), resurrecting a Hindu tradition of philosophical commentary. Asvaghosa's "Awakening of the Faith in the Mahayana" is such a treatise.

The last stage in Mahayana writing was the Tantras, which are central to Tibetan Buddhism. More on them later.

An alternative explanation of the Mahayana sutras as direct inspiration of the eternal Buddha was not stressed much for fear of undermining the original claim that he actually preached these sutras to the gods.

PRAJNAPARAMITA-SUTRAS

Most famous of the early Mahayana scriptures. Literally Perfection (paramita) of Wisdom (prajna). Eleven of them are known: range from 100,000 verse sutra to the 8-line "heart" sutra. Also "Diamond-Cutter" sutra (Vajracchedika; vajra = diamond). See Kalup (2), chap. xv.

Signs of their early composition:1) no Bodhisattvas in the audience; 2) the monks are not ridiculed.

1) Absolute vs. 2) relative understanding of this literature:

1) goal of absolute knowledge and reaching the "other shore"--Nirvana as eternal substance--union with Dharma-kaya.

2) Prajna as a means to understanding that all things are empty. (Kalup [2], p. 154-55: example with the monk Subhuti from the Vajracchedika.) This seems to be Nagarjuna's position. Kalup. supports this by giving a moral, rather than an ontological, interpretation of paramita. This means that this means the perfection of a virtue rather than some perfect absolute reality.

FOUR PHILOSOPHICAL POSITIONS IN BUDDHISM

Absolutism. Concepts and thinking OK, and they give us direct knowledge of the Dharmkaya, Buddha-nature, etc. as ultimate reality. Ashvaghosa is a good example. Kalupahana claims that such a position leads to an ethics of total self-sacrifice that is contrary to Pali Buddhism.

Positive Transcendentalism. Concepts and thinking are inadequate, but we can still have an experience of ultimate reality. It is ineffable and beyond knowledge, but we can still believe in it. Lankavatarasutra is a good example.

Negative Transcendentalism (Deconstruction). Concepts and thinking are all inadequate and intellectual honesty requires us to suspend belief in all knowledge/ontological claims. Nagarjuna is usually placed here.

Experientialism (Buddhist Process Philosophy). Some concepts are OK (but others "tend not to edification") and a limited conceptual framework can gives us a world of process, flux, causality, and change. A personalized ethics here emphasizing a person mean between extremes and a rejection of the ethics of self-sacrifice of Buddhist absolutism.

BUDDHISM'S ANTICIPATION OF POST-MODERN PHILOSOPHY

Pre-Modernism: Primarily described in rituals or mystical experiences that give people the experience of a primordial unity or complete totality. Animism, shamanism, and later forms of mysticism are good examples of pre-modern philosophy.

Modernism: Primarily identified as holding to independent, autonomous selves, and usually connected to a mind (spirit)-body dualism, in which the body is given less value than the spirit. Also a "substance" metaphysics of non-extended thinking things and extended material things, epitomized in Descartes res cogitans and res extensa. Here are the beginnings of dichotomized thinking that pervades Western modernist thinking (1600-1900). Here distinctions between inner/outer, private/public, religion/state, etc. are firmly established.

Post-Modernism: Primarily identified as a movement to overcome the dichotomies of modernism. There are two forms of Post-Modernism:

Constructive Post-Modernism: Reconstruction of reality, self, time, and God as prorocess rather than substance. It is roughly a synthesis of the best elements of prepre-modern and modern thought.

Deconstructive Post-Modernism: Total rejection of any metaphysics--substance or process. It can be described as a weak form of transcendentalism, in which concepts and thinking are inadequate to substantiate any world-view. This position is represented by Jacques Derrida in France and Mark C. Taylor in American theology.

Now: where does the Buddha and Nagarjuna fit in this view: constructive or deconstructive? There may be good reason to place the Buddha in the former and Nagarjuna in the latter, although Kalupahana would place both in the former.

PREMODERNISM, MODERNISM, AND POSTMODERNISM

(Spiritual Titanism, chap. 2)

Let me say at the outset that I am not equating modernism with modernization in the sense of industrialization and urbanization. Modernism is also not necessarily Western and premodernism is not primarily Eastern. Furthermore, modernism is not something new and recent and premodernism something old and ancient. I shall argue that the seeds of modernism are at least 2,500 years old, and they are found in India as well as in Europe. Finally, I contend that we can also discern the beginnings of a postmodernist response among the ancient philosophers, most notably Confucius, Zhuangzi, and Gautama Buddha.

Modernism has been described as a movement from mythos to logos, and this replacement of myth by logic has been going on for at least 2,500 years. Almost simultaneously in India, China, and Greece, the strict separation of fact and value, science and religion was proposed by the Indian materialists, the Greek atomists, and the Chinese Mohists. These philosophies remained minority positions, but it is nevertheless essential to note that the seeds for modernist philosophy are very old. The Greek Sophists stood for ethical individualism and relativism; they gave law its adversarial system and the now accepted practice that attorneys may "make the weaker argument the stronger"; they inspired Renaissance humanists to extend education to the masses as well as to the aristocracy; and they gaveus a preview of a fully secular modern society. Even though maintaining teleology and the unity of fact and value, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle affirmed ethical individualism and rationalism, and Aristotle supported representative government, held by many as one of the great achievements of the modern world.

The crisis of the modern world has led many to believe that the only answer is to return to the traditional forms of self and community that existed before the Modern Age. Such a move would involve the rejection of science, technology, and a mechanistic cosmology. Ontologically the modernworldview is basically atomistic, both at the physical and the social level. The cosmos is simply the sum total of its many inert and externally related parts, just as modern society is simply the sum total of social atoms contingently related to other social atoms. The modern state is simply the social atom writ large on an international scale, acting as dysfunctionally as the social atom does in smaller communities. The modernist view of time is also linear, with one event happening one after the other, with no other purpose than simply to keep on continuing that way. The modernist view of the sacred has been to reject it altogether, or to place God in a transcendent realm far removed from the material world.

The latter solution is the way that some Christian theologians have reconciled themselves with mechanistic science. Authors of TheReenchantment of Science have argued that this reconciliation began early on and that orthodox theologians found mechanistic science an effective foil against a resurgent pantheism (all things are divine) and panpsychism(all things have "souls’) coming out of the Renaissance.

Modernism also gave new meaning to what it means to be a subject, and the primary source of this innovation was the ego cogito of Descartes’ Meditations. The pre-Cartesian meaning of subject (Gk. hypokeimenon; Lat. subiectum) can still be seen in the "subjects" one takes in school or the "subject" of a sentence. In this ancient sense all things are subjects, things with "underlying [essential] kernels," as the Greek literally says and as Greek metaphysics proposed. (As opposed to substance metaphysics,the process view of this pansubjectivism makes all individuals subjects of some sort of experience.) After Cartesian doubt, however, there is only one subject of experience of which we are certain--viz., the human thinking subject. All other things in the world, including persons and other sentient beings, have now become objects of thought, not subjects in their own right. Cartesian subjectivism gave birth simultaneously to modern objectivism as well; and, with the influence of the new mechanical cosmology, the stage was set for uniquely modern forms of otherness and alienation. By contrast the premodern vision of the world is one of totality, unity, and above all, purpose. These values were celebrated in ritual and myth, the effect of which was to sacralize the cycles of seasons and the generations of animal and human procreation. The human self, then, is an integral part of the sacred whole, which is greater than and more valuable than its parts. And, as Mircea Eliade has shown in Cosmos and History, premodern people sought to escape the meaningless momentariness of history(Eliade called it the "terror of history") by immersing themselves in an Eternal Now. Myth and ritual facilitated the painful passage through personal and social crises, rationalized death and violence, and controlled the power of sexuality. One could say that contemporary humankind is left to cope with their crises with far less successful therapies or helpful institutions.

In addition to the terror of history, many premodern people also saw the body and senses as a hindrance to the spiritual life. This view was sometimes connected, as it was in Advaita Vedanta, with the view that the natural world as a whole is illusory or at most only a derivative reality. The alternative to Vedantist monism was a dualism of soul and body; and, in its most extreme forms, Manicheanism and Gnosticism, one is presented with a fierce battle between our spiritual natures and our animal natures.

Interestingly enough, a mind-body dualism characterizes some of modern thought, but it is formulated in a much more subtle and sophisticated way; and, most importantly, matter is not considered the embodiment of evil. Modern philosophy generally separates the outer from the inner, the subject and the object, fact and value, the is and the ought, science and faith, politics and religion, the public from the private, and theory from practice. Following Descartes' insistence on a method of reducing to simples and focusing on clear and distinct ideas, modern humans have made great strides conceptually and theoretically. The practical application of modernism has extended the rule of science and conceptual analysis to all areas of life: personal machines of all sorts, a fully mechanized industry, and centralized bureaucratic administration. Critics of modernism observe that it is a great irony that the modern state celebrates human rights but at the same time its state organization has destroyed personal autonomy. It has also eroded the intimate ties of traditional community life, and has threatened the ecological balance of the entire planet.

Constructive postmodernists wish to reestablish the premodern harmony of humans, society, and God without losing the integrity of the individual, the possibility of meaning, and the intrinsic value of nature. They believe that French deconstructionists are throwing out the proverbial baby with the bath water. The latter wish to reject not only the modern worldview but any worldview whatsoever. Constructive postmodernists want to preserve the concept of worldview and propose to reconstruct one that avoids the liabilities of both premodernism and modernism. They would be very comfortable with Graham Parkes' interpretation of Nietzsche's Three Metamorphoses as representing immersion, detachment, and reintegration. They could take the camel stage as the symbolizing the premodern selfimmersed in its society; the modern lion as protesting the oppressive elements of premodernism but offering nothing constructive or meaningful in return; and the child as representing the reintegrative task of constructive postmodernism. Parkes explains:

The third stage involves a reappropriation of the appropriate elements of the tradition that has been rejected. . . . The creativity symbolized by the child does not issue in a creation ex nihilo, but rather in a reconstruction or reconstrual of selected elements from the tradition into something uniquely original.

It must stressed that Parkes is attributing this view to Nietzsche, who is generally taken to be the 19th Century's leading prophet of deconstructive postmodernism.

Constructive postmodernists are also concerned about a logocentric society and the dominance of calculative and analytic reason, but instead of the elimination of reason altogether, they call for a reconstruction of reason. A working formula would be the following triad: mythos > logos as analytic reason > logos as synthetic, aesthetic, dynamic reason. The best example of aesthetic reason is the unity of fact, value, and beauty that we find in Confucian virtue ethics--viz., the act of self-cultivation is analogous to the making a gem stone. A more recent example of a reconstructed logos is found the new "logic" of Western art since the late 19th Century. Cezanne rejected the classical (read logocentric) perspective and initiated a revolution that opened up new ways of looking at the world. Drawing on Japanese, African, and other non-Western themes at the turn of the century, artistic revolutionaries synthesized the premodern and modern in the same way that Gandhi did in his social and political experiments. In a chapter entitled "The Reenchantment of Art: Reflections on the Two Postmodernisms," Suzi Gablick presents both deconstructive and reconstructive examples of contemporary art and finds that the latter movement is a continuation of the artistic revolution just described. Gablick states that "reconstructionists . . . are trying to make the transition from Eurocentric, patriarchal thinking and the "dominator" model of culture to a more participatory aesthetics of interconnectedness, aimed toward social responsibility, psychospiritual empowerment, deep ecological commitment, good human relations, and a new sense of the sacred. . . ." This view of art emphatically rejects the modernist view of art for art’s sake, which is yet another result of the alienation of the private and public that we find in modern culture.