XUNZI (298-238 BCE)

John Knoblock of the University of Miami argues for an earlier birthdate of 310 and a later death at 219.

In what follows the Burton Watson translation of the Xunzi will sometimes be cited. Hsün Tzu: Basic Writings (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963). Eric Hutton's translation in Ivanhoe and van Norden will be cited for Chap. 21.

Xunzi is closer to Confucius on learning than Mencius is. The doctrine of the four sprouts allows Mencius to overemphasize our intuitive capacities to be moral. Because of this Mencius thought that learning was "easy," while Confucius and Xunzi would say that it is very difficult. The latter would also agree that it is thoroughgoing learning of concrete things and relations.

If learning is so easy, asks Xunzi, why would be need the sage kings? With our four sprouts we should know what to do morally without any external guidance.

P. J. Ivanhoe, "A Happy Symmetry: Xunzi’s Ethical Thought," Journal of the American Academy of Religion 59:2, 309-322.

Because of his belief that human nature is evil, Xunzi is sometimes called a Confucian Calvinist, but he is closer to Thomas Hobbes. The differences, however, are still many. Although both believed that humans in a "state of nature" would descend into a state of barbarism, Xunzi believed that good moral education through li and yi (which is "external" for him just as it was for Gaozi) would save us. Hobbes of course thought that humans needed a strict social contract with an absolute monarch (who, by the way, was above the law!) to rule over them. Hobbes was much more like the Chinese legalists. Curiously enough, Xunzi’s most famous disciples Li Si and Han Feizi became great legalist philosophers.

A 308 student has described Xunzi's idea of an evil nature as a slightly slopping road and some may choose to take the easy way down towards evil. But with a little effort, li, and good moral and political leaders there is a very good chance that most people will choose the steady climb up the slope to a better humanity. Notice how this relates to Mencius claim, in response to Gaozi, that the its natural for water to flow downhill. Xunzi has simply chosen to call the analogous inclination in humans the inclination towards evil.

Schwartz, p. 296: Another contrast with Hobbes and the Confucians. There is not a hint in Hobbes’ description of the absolute monarch about his moral cultivation or the necessity of his being virtuous at all. His is a rule of law not personal virtue. Xunzi of course disagrees: "The law cannot stand alone. The various categories [of Li?] cannot implement themselves. It is only when one obtains the [right] man that they can be actualized. Without the right man, they are lost. The law is the principle of good order. The noble man is the source of the law" (quoted in ibid.) Xunzi’s criticism of the legalist Shendao would fit Hobbes’ king very well: "He despises self-cultivation and has a predilection for creating [new] laws. . . . He exalts law and is without law" (quoted in ibid., p. 319).

"Man possesses energy, life, intelligence, and, in addition, a sense of duty (yi)" (chap. 9, Watson, p. 45). Does this mean that yi is innate? Or does "in addition" literally mean that it is added by moral instruction? By the way, Ivanhoe translates yi as "social norms." Schwartz (p. 295) believes that Xunzi order of putting Li before Yi is deliberate and it is consistent with his view that only after internalizing Li will we know what the right (yi) thing to do is.

Ivanhoe points out one more aspect of Xunzi’s thought which does not appear in the West until the 20th Century. Moral education would also protect nature from human encroachment. (Like all ideals this was not followed only imperfectly in ancient China.) Ivanhoe and Machle are the only Confucian scholars who see this, however. Since the regularities of nature make nature flourish, so, too, will the patterns of social norms also make human flourish. Ivanhoe thinks that Xunzi, more than any other Confucian philosopher, sees the vital connection between keeping both nature and humans in balance. This human and nature connection is the "happy symmetry" of Ivanhoe’s title. Although Xunzi disagrees with the Daoists on a total wu wei, Ivanhoe sees the influence of Daoist naturalism in Xunzi’s extension of the Dao to nature.

Ivanhoe, 318: Xunzi ultimately is very conservative. The Li of the sage kings is immutable and it will serve for all times and places? Since music has unchanging harmonies, then Li will be unchanging as well (Chapter 20, Watson, p. 117). This represents a god-like (shen) order.

Nevertheless, Ivanhoe believes that Xunzi’s position is more flexible if times turn very bad for human beings. He would, according to Ivanhoe, allow more exceptions to Li than Mencius, where Li and the other virtues are built into our nature. Does this again show Xunzi’s proto-utilitarianism, that Li is causing more pain than pleasure, then certain adjustments have to be made. Ivanhoe’s best point is the hypothetical that if the sages had brought Li into being during very bad times, then it would seem that Li would have been different. How would this then match up with the natural harmonies of music and the rest of nature?

Because of the fact that human nature tends to evil, we cannot expect people to take to virtue with ease or joy as Mencius thought. Therefore, people will first realize that morality has instrumental value, that to be moral is in our own self-interest. Only later we will learn to see the value of the virtues as ends in themselves. Again Confucius and Mencius condemned those who became moral because of advantage or profit.

Chapter One. The physiognomy of virtue: "The learning of the gentleman enters through his ears, fastens to his heart, spreads through his four limbs, and manifests itself in his actions. His slightest word, his most subtle movement, all can serve as a model for others" (Hutton, I&N, 250). In the petty person it only goes from ears to mouth and not to the entire body. Reading all the classics cannot substitute for emulating the virtuous person.

Does Xunzi break with the basic Confucian view of human nature, namely, to be human is to be together with other humans? He seems to have a more Western idea that human uniqueness lies in our mental capacities to make distinctions. But interestingly enough, the most important distinctions are the social ones. Animals don’t show proper affection according to the five relationships. In other words, the most important distinctions are the ones made by li and yi. (See Chap. 5 of the Xunzi). Yi, by the way, has a very different meaning, principally because it is external rather than internal. As Hutton says (I&N, 251note) it now means social standards that are internalized as the virtue of right action. But there is some of Confucius' notion of personal appropriation when he speaks of doing li "your way" rather than the strict guidelines of the classics (I&N, 252). Note also this passage: "If he has the proper model but does not fix his intentions on its true meaning, then he will act too rigidly" (256).

The artisan analogy for the origins of morality (Chan, p. 130; Watson, p. 160). When a potter makes a pot out of clay, the product comes from his conscious activity, not from his nature. Similarly with the product called morality. "The sage gathers together his thought and ideas, experiments with various forms of conscious activity, and so produces rituals and social norms (li and yi) and sets forth laws and regulations." There is almost a proto-utilitarian idea here reminiscent of the Mohists, viz., that morality will be those rules that maximize human happiness.

A calm and peaceful mind will be content with mediocre beauty and sounds? (Watson, p. 155) Confucius also said that the junzi will many times be content with a simple, even rough life. The assumption, however, is that part of her education was beautiful objects and sounds. All Confucians, including Xunzi, emphasize the importance of the arts for moral education.

Xunzi is more "spiritual" than Confucius? Yes, if the number of positive references to shen is any indication. Tian as preemient shen (Machle); shen as subordinate spirits (essences) in the cosmos—for each of the 10,000 things; shen = Gk. psyche = Heb. nephesh. Human soul somehow related to xin—heart-mind. Xin is the "heavenly" ruler of the body.

Tian produces the 10,000 things by means of subordinate shen, but it does not and cannot order human affairs. Therefore, the Confucian program is yu wei not wu wei. Xunzi’s work could be called a "Hymn on Yu-wei not Wu-wei." Human action centered not Heaven centered.

CHAPTER 21: UNDOING FIXATION (Hutton translation in I&N)

True knowledge requires a holistic understanding of things, not from a single fixed perspective. Mozi was "fixated on the useful and did not understand the value of good form" (li as aesthetic and moral?). (Watson has "the beauties of form.") The Daoist Zhuangzi "was fixated on the Heavenly and did not understand the value of the human." In his translation Watson quickly explains that Heaven here actually means nature in spontaneous action. Xunzi believes that humans should do more than just harmonize with natural forces.

273, bottom: Xunzi introduces a principle that will become central to Neo-Confucianism: "As for the Dao itself, its substance is constant, yet it covers all changes. No one aspect is sufficient to exhibit it fully." (Neo-Confucianism typically phrased this as "li** is one, but its manifestations are many."

274: Confucius was not fixated and was wise and benevolent; his virtue was equal to that of the Duke of Zhou, and "his name ranks with those of the three kings."

The sage "lays out all the then thousand things and in their midst hangs his scales over them." Allusion to technological control of nature? No, because he explains the scales are the Dao itself. As we will see below, one uses the Dao of Heaven (li**) as a model for li and yi.

274, bottom: Heart-mind know the Dao through "emptiness, single-mindedness (Watson has "unified"), and stillness." Daoist influence here? Especially with the dialectic of opposites such as the heart-mind is always holding something but it is empty, always moving yet still. Watson's resolution: the mind is filled with memory but can always hold more? But Hutton goes with the original character which means "focus," and concludes that having an empty heart-mind means being receptive. Even though the heart-mind is constantly moving it must be still, too, so as not to be overcome with the disorder of dreams and errant thoughts.

275: Spiritual Titanism? Those who have the three qualities above have "great clarity and brilliance." And with these qualities one "sets straight Heaven and Earth, and arranges and makes useful the ten thousand things. . . . His brilliance matches the sun and the moon. His greatness fills all the eight directions." This is the zhi ren and there is no fixation in him.

276: A indirect commentary on Confucius' declaration that the junzi is "not an implement" (2.12) and proposes that the one who knows the way will not have any specific skills. "One who is expert in regard to things merely measures one thing against another. One who is expert in regard to the Dao measures all things together."

277: Stillness of heart-mind is like still water. Daoist image, but no direct connection with previous ideas of emptiness and stillness. The point of the metaphor seems to be more the clarity of the water rather than its stillness.

XUNZI ON LI AND LI**

There is a cosmic order or logic (li**) that the sage-king, by the use of his xin, can make into li and thereby establish culture (wen). For Xunzi only the cosmic li** is natural, while the second is conventional, human made on the model of the cosmic order. Mencius definitely thought that both were natural. Confucius’ position is not entirely clear, but he does say that Heaven is the source of the virtue that is in us.

Veins of jade and Plato’s joints of a carcass. Phaedrus 265de: "We are enabled to divide into forms, following the objective articulation [natural joints]; we are not to hack off parts like a clumsy butcher." Plato's dialectician knows the veins of logos across the face of the real, just as an expert butcher knows the joints of an animal carcass. Similarly, the Confucian sage knows the veins of li** which he can make into the order and structure of li.

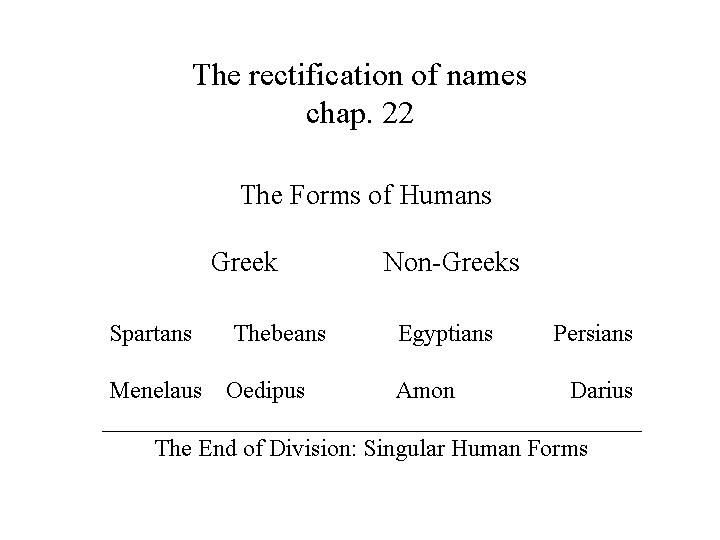

In Chap. 22 Xunzi is disturbed by the introduction of strange words that have ambiguous referents. This has led to a confusion of right and wrong in his day. To counter this chaos he reaffirms Confucius' project of the "rectification of names," beginning with ruler is rule, husband is husband, elder brother is elder brother, etc. Plato's method of division and collection parallels Xunzi's comprehensive attempt at the rectification of all names. In Chapter 1 Xunzi implies that the many li can be divided up in the same way: "Rituals are the great divisions in the proper model for things; they are the outlines of the proper class of things. And so learning comes to ritual and then stops, for this is called the ultimate point in pursuit of Dao and De" (Hutton, I&N, 250).

We have gone from the most abstract concept of humans to the most particular. Once we reach a particular person, we cannot go any further. Compare with Xunzi (Chan, p. 126 middle.) Compare also with Duns Scotus (13th C. Christian philosopher) who would argue that such an analysis proves that there is a general universal for humans and also a specific form that one might call Bill Clintoneity, Confuciusness, George W. Bushness, etc. There are conventional (humans make them up) on either end, but there are real limits that humans do not create at either end of this process.

Since earlier Confucians did not offer such a detailed analysis of names, commentators suspect Mohist influence on Xunzi here. At any rate, Xunzi is a conventionalist on the question of the relation of names to things. Most all philosophers agree that names are simply handy tags that we fashion out of natural languages to differentiate one thing from another. What may not be conventional are the larger categories (or specific ones if Scotus is right) that things naturally fall into. Plato called them forms and other European philosophers called them essences. The Confucians were called them li** in the cosmic sense. Many philosophers East and West believe that these are also conventional.

Xunzi’s belief was that the more exact we drew the categories the more firm we would be about the proper distinctions among human beings and the better off society would be. Nature runs according to these categories wu wei, but human beings are not so lucky. As Schwartz points out (p. 313), Xunzi pretty much sticks to the human world in his categorical analyses, while the Mohists tried to classify everything. This fact mitigates the charge that Xunzi is some sort of proto-scientific humanist and certainly undermines any sort of proto-technologism. Furthermore, Xunzi does not follow the Mohists in their keen interest in logical argument.

CHAPTER 23: WHAT’S IN ORIGINAL NATURE?

Schwartz, 291: Is chapter 23, as some scholars say, a later interpolation such that "human nature is evil" is not actually Xunzi’s position at all? Schwartz does not believe this to be the case.

Schwartz, 293: In Xunzi the word xin is more properly translated as "mind" as the rational controller of the desires and the passions. The sage kings differed not a wit from the masses in their basic natures; they simply used their minds better in sizing up the world and what needed to be done.

Could there have been Mohist influence on Xunzi’s concept of xin? Their view of the mind was very rationalistic and they were also full-blown utilitarians, i.e., humans should always act to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. But Schwartz argues against a utilitarian interpretation of Xunzi on pp. 299-300.

Chan, p. 128: "desires of ear and eye and likes sound and beauty." Analogy of li: music is not natural but must be produced by a composer. The Taoists will disagree, especially Zhuangzi, who believes in a natural music.

p. 130: "the eye desiring color, the ear desiring sound, the month desiring flavor, the heart desiring gain, and the body desiring pleasure and ease." These are not produced by "effort" like music and li but come naturally. The nature of the sage is common with us but his effort is superior.

p. 130 bottom: natural for humans to love profit and seek gain. Only li will save the selfish brothers in the story.

p. 129 (I&N, 286). An argument against the followers of Mencius:

Assumption: "Clear vision and distinct hearing cannot be learned." If so, then there is no need to learn goodness. Reductio ad absurdum.

p. 131: Xunzi: if we are originally good, why are sages and morality necessary? Mencius answer might have been: because we have only sprouts and not full-grown saplings of virtue.

But a reductio back on Xunzi: "Man's nature (xing, sheng*) is is the product of Nature (Tian)." Tian, which is good, gives us an evil nature?

The younger deferring to the elder and the son deferring to the father: "these two lines of action are contrary to original nature and violate natural feeling." But this is li-yi. So these two must be created and not original in us.

p. 132:

sharping bending transforming specific forms Li

____ . ________ . ___________ . ________ . ______

metal crooked wood evil nature clay human nature

straight is not inherent in crooked wood; the pot is not inherent in the clay; therefore, goodness is not inherent in humans. How about the veins of li giving rise to li*? Xunzi’s own image. Potential goodness? How about Xunzi's admission that one can find straight grained wood?

p. 133 bottom: can any person become a sage? Yu preferred rather than Yao and Shun. Chan: was it because Yu was the "doer" (technologist) rather than the thinker-moralist?