The Hollow Hearing Effect

“I just do not know if I have it in me to write another paper” were one student’s words midway through my Hosea exegesis course. By this time, I was on my third semester of pandemic teaching. Zoom fatigue had set in alongside our unceasing grief for the daily Coronavirus death tolls. Hearing each other in a virtual space that seemed coerced and yet routine was not limited to a spotty Wi-Fi signal or faulty audio equipment. Our hearing—that kind we learn from—had fallen numb.

Pre-pandemic, the design and pedagogical approach to my Hosea exegesis course had reached a sweet spot. I had a good learning balance between group work (contextualizing the biblical critic and reading in community) and individual final projects. As for the psychosocial dynamics of this space, it was easy to read the feeling states in the room—enervation, anxiety, but also, surprise, discovery, or intrigue. And by midway through the course, everything in my syllabus usually went as planned, barring a few late papers. As such, hearing to learn and learning to hear seemed to work harmoniously with our embodied practices in the classroom.

The abrupt shift to pandemic teaching posed unique challenges to my hearing-learning reflexes. Upon reflection, the issue was not auditory but rather a stale hollowness of presence or what I call “the hollow hearing effect.” Arriving at this diagnosis of the learning experience was, indeed, a process, beginning with the shocking midsemester flip to online teaching to running a new learning platform to revamping my syllabi for a new virtual world of teaching Bible. Soon, the rhythms of my synchronized classroom felt random and sluggish, in part because of our connectedness to the globe’s misery but disconnectedness on Zoom.

Then comes spring 2021, the semester of my Hosea exegesis course. Going in, I recall feeling optimistic about my redesigned syllabus. Instead of my usual “reading in community” group assignment, I had students contribute asynchronously to a video community commentary. Here, students created a ten-minute video in which they read their English translation of the assigned Hebrew verse, highlighted one major poetic feature, discussed two contrasting interpretations, and lastly applied their reading to a contemporary issue (e.g., trauma, migration, empire, gender, violence, justice). Below each uploaded video commentary, students had the opportunity to pose questions and offer constructive feedback. Each week, their online community commentary unfolded according to plan. Although their feedback fell between modest and missing, their videos showed a genuine and critical engagement with Hosea. I was especially moved by their applications of Hosea to various contemporary issues (white privilege, anti-black violence, family separation at the Texas-Mexico border, reproductive justice, the pandemic, etc.).

Despite the decent success of this assignment, students were still coping with the constraints and hardships caused by COVID-19. While I could help them decipher the trauma in Hosea, I had difficulty reading their own learning woes online. By week ten, it finally became apparent that my syllabus’ mechanical precision did not exempt students from the grief-inducing complexities of a global pandemic. Their day-to-day angst of forced immobility and family separation were coupled with a weekly dose of prophetic texts rife with trauma, violence, and abuse. Add to this their application of Hosea to contemporary traumas, and the results were a learning breakdown.

Once I was made aware of this, I felt like I do when I travel with my family through an international airport. Usually, I am leading the way to our connecting gate. Without looking back, I soon go from a steady walk to a marathon-style stride. Though I arrive on time, my family is nowhere to be seen. Out of breath, they finally arrive asking angrily, “Why didn’t you stop for us?” Hence, though I made it to week ten of my syllabus, my students were “crawling towards the finish line.” Unlike my airport marathon, I decided to put the brakes on my syllabus two weeks before my Hosea exegesis course ended.

As a remedy to my students’ learning woes, I decided to offer them a second option for their final project. In lieu of an academic exegesis paper, students could submit an art exegesis project. Indeed, my recourse to art was not some random contrivance. From the standpoint of prophetic literature, the art of poetry served as a viable care-strategy for coping with the traumas of imperial conquest. Moreover, artmaking and the traumas of forced migration have been central to my advocacy work in the US-Mexico borderlands (see Arte de Lágrimas: Refugee Artwork Project). Thus, to turn to art for a final project made sense at a deeper level.

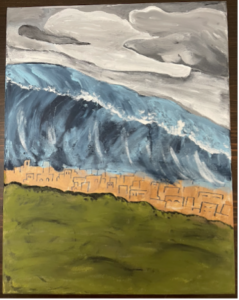

In the end, every student in the course submitted an art exegesis project, which included original art, an art talk, and reflection. Here is an example of one student’s triptych art exegesis (oil paintings):

“I Will Tear”

(Hosea 5:14)

“I will love them freely…And lengthen his roots”

(Hosea 14:4-5)

“And Shall Arise among your people”

(Hosea 10:14)

Among the responses, one student stated, “It revealed to me things about the text and about myself that I don’t think I would have seen doing my standard mode of exegesis.” As their teacher, it gave me a way of hearing my students that was far from hollow but rather healing.

Leave a Reply