The “Holy Fool” in Islam

In all of the world’s religions, one finds the notion of a “holy fool”: an individual who transcends societal conventions with his/her ridiculous behavior and unpredictable manner of revealing moral truths. For my “Religious Heritage of Islam” and “Religions and Cultures of the Middle East” courses, one of my favorite class exercises involves having students read and discuss a variety of stories and sayings about one of Islam’s most famous “holy fools,” Mullah Nasruddin. Nasruddin is a legendary 13th-century satirical figure who is claimed by many – including Afghans, Turks, Kurds, Uzbeks, and Iranians – to be their own. In Arabic contexts, this figure is often known as Joha. Thriving well along the boundaries of traditionally Muslim societies, he remains the inspiration for folklore in places as varied as Georgia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Azerbaijan, and Sicily.

Nasruddin is characterized as devout yet irreverent, unpredictable yet consistently foolish, comically inept yet clever. In this exercise, I help my students to understand how stories about Nasruddin use humor to represent and critique Islamic religious and cultural norms, customs, beliefs, and institutions, and to destabilize widespread assumptions. By presenting lessons in a humorous way, Nasruddin holds up a lens to how people flatter political and religious leaders and tell them what they wish to hear. He takes on the role of the fool, which allows him to be subversive without posing a real threat to venerated systems of authority or to pious conventions that have been dampened by empty formalism.

While tales about Nasruddin defy easy classification, I work with students to explore a variety of themes that can be found in them. One theme concerns what I call the “bazaar haggling mentality,” which can be described as “outrageous reasoning” that is nonsensical yet amusing and which challenges the status quo. It also can reflect an ego-centric attitude in that the individual seems driven by his wants and idiotic yet transparent about his foolishness. Here are some examples:

The Reason

The Mullah went to see a rich man.

‘Give me some money.’

‘Why?’

‘I want to buy … an elephant.’

‘If you have no money, you can’t afford to keep an elephant.’

‘I came here’, said Nasruddin, ‘to get money, not advice.’(13)

Tit for tat

Nasruddin went into a shop to buy a pair of trousers.

Then he changed his mind and chose a cloak instead, at the same price.

Picking up the cloak he left the shop.

‘You have not paid,’ shouted the merchant.

‘I left you the trousers, which were of the same value as the cloak.’

‘But you did not pay for the trousers either.’

‘Of course not,’ said the Mulla – ‘why should I pay for something that I did not want to buy?’ (24)

Another theme explored is Nasruddin’s critique of the Insha’Allah mentality found in traditional Muslim societies, which have tended to prioritize theological preoccupation with divine will over philosophical reflection on observable causes. This tendency coincides with a cultural inclination to assign a large role to chance or fate, and can involve minimizing the significance of human responsibility in relation to divine causality. Here are some examples:

Assumptions

‘What is the meaning of fate, Mulla?’

‘Assumptions.’

‘In what way?’

‘You assume things are going to go well, and they don’t – that you call bad luck. You assume things are going to go badly and they don’t – that you call good luck. You assume that certain things are going to happen or not happen – and you so lack intuition that you don’t know what is going to happen. You assume that the future is unknown. ‘When you are caught out – you call that Fate’. (20)

If Allah wills it

Nasruddin had saved up to buy a new shirt. He went to a tailor’s shop, full of excitement. The tailor measured him and said: ‘Come back in a week, and – if Allah wills – your shirt will be ready.’ The Mullah contained himself for a week and then went back to the shop. ‘There has been a delay. But – if Allah wills – your shirt will be ready tomorrow.’ The following day Nasruddin returned. ‘I am sorry,’ said the tailor, ‘but it is not quite finished. Try tomorrow, and – if Allah wills – it will be ready.’ ‘How long will it take,’ asked the exasperated Nasruddin, ‘if you leave Allah out of it?’ (29)

In contrast to the previous theme, another theme is Nasruddin’s challenges to rationalism. Here we find Nasruddin keeping philosophers and worldly, rational thinkers on their toes by using inconsistent logic:

Inscrutable Fate

Nasrudin was walking along an alleyway when a man fell from a roof and landed on his neck. The man was unhurt; the Mullah was taken to hospital. Some disciples went to visit him. ‘What wisdom do you see in this happening, Mullah?’ ‘Avoid any belief in the inevitability of cause and effect! He falls off the roof – but my neck is broken! Shun reliance upon theoretical questions such as: “If a man falls off a roof, will his neck be broken?”’(26)

Prayer Is Better Than Sleep

As soon as he had intoned the Call to Prayer from his minaret, the Mulla was seen rushing away from the mosque. Someone shouted, "Where are you going, Nasruddin?" The Mulla yelled back, "That was the most penetrating call I have ever given. I’m going as far away as I can to see at what distance it can be heard." (98)

The Value of Truth

‘If you want truth,’ Nasruddin told a group of Seekers who had come to hear his teachings, ‘you will have to pay for it.’ ‘But why should you have to pay for something like truth?’ asked one of the company. ‘Have you not noticed,’ said Nasruddin, ‘that it is the scarcity of a thing which determines its value?’ (90)

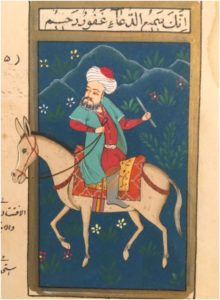

By providing my students with handouts listing these quotes, I then ask them to work in groups to identify themes that relate in some way to larger questions of Islamic theology and philosophy (for example, traditionalist and rationalist understandings within Islam) that we have discussed in previous class sessions. We then hold a larger group discussion to discuss these themes as well as ways in which a character such as the “holy fool” can hold up a mirror to society or remind people never to be too sure about their assumptions. Lastly, I also like to project different visual representations of the Mullah, and ask the students what do they see in images such as the following miniature.

As the students immediately notice, the Mulla is riding backward on a donkey I ask them why, and then I explain how this miniature depicts a well-known story of Nasruddin riding his donkey backward while leaving a village that he had visited. When asked the reason, he simply responded: “I did not want to disrespect the people by having my back to them.”

In my experience, the “holy fool” offers students a fresh way of experiencing Islamic religion and culture, breaking through stereotypes to reveal humanity and humor as well as subtle wisdom and capacity for satire. Many students have testified that exercises involving stories of Mullah Nasruddin are rewarding and valuable, and allow them to think critically about larger issues even while experiencing a deeper respect for the richness of the culture from which the stories emerged. Mullah Nasruddin’s tendency to raise questions but not necessarily answer them helps to open up space for deep questioning and laughter alike.

I would like to conclude with one last story, giving the Mullah the last word.

The Mulla lost his key and was looking for it under a street lamp. A man noticed that the Mulla was looking for something and stopped to help him find it. After an hour of looking, the man asked the Mulla if he could remember the last time he saw the key and the Mulla replied, ‘In my bedroom.’ The man angrily responded by stating ‘Then why are you looking for it here?’ ‘Because,’ Nasruddin told the man, ‘There is much more light here.’

**All quotes in this blog post come from I. Shah (1971). The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasrudin. New York: E. P. Dutton.

My wife and I stumbled over here different website and thought I might as well check things out. I like what I see so now I’m following you. Look forward to checking out your web page repeatedly InshaAllah.

I follow this website. And I read your blog stories regularly.

Ramadan or Ramazan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting, prayer, reflection and community.

Ramadan is a most beautiful month. Islamic Prayer is the most important part of Ramadan Kareem.

I must say that Islam is a perfect religion and Ramadan is one of the holy months in Islam that is not only beneficial for us spiritually but also body wise. Happy Ramadan to Everyone!

This blog on the “holy fool” character of Mullah Nasruddin is a captivating exploration of the intricate themes and cultural significance found within Islamic folklore. The author does an excellent job of illustrating how Nasruddin’s tales utilize humour and satire to critique societal norms, challenge assumptions, and prompt critical thinking.

The inclusion of various anecdotes and examples truly brings Nasruddin’s character to life, showcasing his irreverent yet clever nature. I particularly appreciated how the author delved into different themes present in the stories, such as the “bazaar haggling mentality,” the critique of the Insha’Allah mentality, and Nasruddin’s challenges to rationalism. These themes not only provide insightful commentary on Islamic theology and philosophy but also serve as universal reflections on human behaviour and belief systems.

The author’s approach of engaging students in group discussions and analysis of the themes and visual representations of Nasruddin adds an interactive element to the learning experience. By encouraging students to question assumptions and explore the deeper meanings behind the stories, the author fosters critical thinking and a deeper appreciation for the cultural richness embedded within the tales.

The final story about Nasruddin searching for his lost key under the streetlamp is a perfect way to conclude the blog. It encapsulates the essence of Nasruddin’s character, using wit and irony to highlight the human tendency to focus on what is visible and convenient rather than addressing the root of the issue.

Overall, this blog post provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of Mullah Nasruddin and the enduring appeal of his stories. It serves as a reminder that humour and satire can be powerful tools for social commentary and encourages readers to embrace deep questioning and laughter as essential elements of intellectual exploration. Well done!

Fascinating article on the ‘holy fool’ in Islam and the wisdom wrapped in humor through Mullah Nasruddin’s tales. It’s remarkable how these stories challenge assumptions and offer insight into cultural norms and religious ideas. If you’re looking for an interesting take on aligning routine with spiritual practices, here’s a helpful resource for accurate prayer times: https://prayerstimedubai.com.

Mullah Nasruddin’s stories offer a refreshing way to challenge norms and reflect on societal behavior, all while keeping us entertained. His unpredictable logic and humorous wisdom provide unique insights into human nature, encouraging us to question assumptions in a light-hearted yet meaningful way. Visit https://starbucksmenuprice.net/

Nasruddin’s stories are a brilliant reminder of how humor can challenge our assumptions and offer unexpected wisdom. Much like his approach to life, gaming can be full of surprises. For those looking to Enhance Roblox gameplay, using tools like Solara Executor can open up new opportunities, giving players the flexibility and creativity to navigate their virtual worlds with confidence and agility.

Mullah Nasruddin’s stories offer a refreshing way to challenge norms and reflect on societal behavior, all while keeping us entertained. His unpredictable logic and humorous wisdom provide unique insights into human nature, encouraging us to question assumptions in a light-hearted yet meaningful way. Visit https://starbucksmenusprices.com/

While entertaining us, Mullah Nasruddin’s novels provide a novel approach to question social mores and consider how society behaves. His erratic reasoning and witty insight offer fresh perspectives on human nature and inspire us to critically examine presumptions in a fun yet significant way. Take a look at starbuckmenusprice.com

Thanks for sharing informative content. It helps me a lot.

Mullah Nasruddin is a satirical figure in Islamic folklore known for his humorous and unpredictable behavior, which challenges societal and religious norms. His stories critique authority and conventions through wit, often using “outrageous reasoning” to destabilize assumptions, like in the “bazaar haggling mentality” where he justifies absurd actions

This insightful post highlights how Mullah Nasruddin, as the “holy fool,” uses humor and satire to challenge societal norms and provoke deeper reflections on faith, fate, and rationality in Islamic culture.

This article offers a thought-provoking look at the concept of the “holy fool” in Islam through Mullah Nasruddin. His humorous and subversive behavior challenges societal and religious norms, encouraging critical thinking about fate, authority, and rationalism. The use of Nasruddin’s stories in the classroom helps students engage with complex theological debates in a fun and accessible way. This approach not only deepens their understanding of Islamic culture but also promotes reflection on the limits of certainty and assumptions.

In the context of teaching, tools like YAS downloads could enhance the learning experience by providing resources or interactive content that complement Nasruddin’s stories. YAS software might support the integration of multimedia or provide digital archives of similar satirical works, enriching the exploration of Islamic humor and philosophy. Overall, the article highlights how humor can be a powerful tool for questioning and learning, with digital resources further enhancing student engagement.

This article provides a compelling analysis of Mullah Nasruddin’s role as a “holy fool,” illustrating how his humor challenges societal norms and religious conventions. The thematic breakdown, supported by well-chosen anecdotes, effectively highlights his satirical wisdom. A well-structured and insightful read!

Mullah Nasruddin is a sarcastic figure in Islamic fables known for his entertaining and unusual way of behaving, which challenges cultural and strict standards. His accounts evaluate authority and show through mind, frequently utilizing “over the top thinking” to undermine presumptions, as in the “market wrangling attitude” where he legitimizes ludicrous activities

Insightful read! The concept of the holy fool in Islam beautifully highlights how wisdom can be found in unexpected forms. A thought-provoking perspective on spirituality and societal norms

A fascinating exploration of the holy fool in Islam! It’s intriguing how unconventional figures can embody deep spiritual wisdom and challenge societal perceptions.